Keylor, W. R., The Twentieth-Century World: An International History, Oxford

University Press, 2003, ISBN-10: 0195168437 (paperback, 2005)

If you are a student who needs to cram the history of international relations in the XX century in a single night before the test, this is the book you need. Judging by its 5th edition, this is the opinion of many. It is cursory, but accurate. Moreover, unlike most other English-language sources, Keylor’s treatise gives ample consideration to political events in the regions outside of the Euro-Atlantic sphere, such as East Asia or Latin America.

Priorities, though, are strange. The whole World War II and the Holocaust occupy 18 pages out of six hundred, fewer than the 90s dissolution of Yugoslavia. Maps are good, but statistical tables are sketchy, mostly geared towards American trade relations.

Wednesday, December 26, 2007

Monday, December 17, 2007

Max Boot, War Made New: Technology, Warfare, and the Course of History: 1500 to Today, Gotham, ISBN-10 1592402224

Max Boot, War Made New: Technology, Warfare, and the Course of History: 1500 to Today, Gotham, ISBN-10 1592402224

This is Ramsfeldianism writ large. Almost all correct observations are lifted from J. F. C. Fuller, a Nazi sympathizer, who was also a very intelligent and well-educated observer (why all plagiarists chose either well-known or second-rate works is a mystery to me). Sometimes, he recycles Fuller’s dotage absurdities such as his exaggerated belief in purely psychological impact of new weapons, as the reason for their adoption.

As is typical for all neocons, Boot worships Prussian military tradition. Yet, since Frederic the Great, there was only one war (Franco-Prussian, 1870-1871), in which German military machine performed creditably against an opponent of comparable technical sophistication. This is the perpetual PR of the German generals inducing them to write long, self-serving memoirs after each lost war, explaining how they had nearly won it, and the perpetual habit of British journalists and American military academy teachers to believe every word of it, which obscures their, usually dismal, record on the battlefield.

His adulation for these “goose-stepping morons” (apt description by Indiana Jones) ends only with similarly garbled paeans for the US military. Nearly all innovations in military weapons and tactics since circa the Civil War are ascribed to Americans, or at least Anglo-Saxons, as if the author was schooled in late Stalin’s Russia, where all technical or exploration achievements ought to be backdated to Russian protagonists. The purpose of this book is to justify apparently insatiable appetite of the Pentagon, after the Cold War, to procure new and expensive weapons systems without any consideration for their tactical suitability or sound technical design, on the basis of pure “gut feeling” by the military bureaucrats.

This is Ramsfeldianism writ large. Almost all correct observations are lifted from J. F. C. Fuller, a Nazi sympathizer, who was also a very intelligent and well-educated observer (why all plagiarists chose either well-known or second-rate works is a mystery to me). Sometimes, he recycles Fuller’s dotage absurdities such as his exaggerated belief in purely psychological impact of new weapons, as the reason for their adoption.

As is typical for all neocons, Boot worships Prussian military tradition. Yet, since Frederic the Great, there was only one war (Franco-Prussian, 1870-1871), in which German military machine performed creditably against an opponent of comparable technical sophistication. This is the perpetual PR of the German generals inducing them to write long, self-serving memoirs after each lost war, explaining how they had nearly won it, and the perpetual habit of British journalists and American military academy teachers to believe every word of it, which obscures their, usually dismal, record on the battlefield.

His adulation for these “goose-stepping morons” (apt description by Indiana Jones) ends only with similarly garbled paeans for the US military. Nearly all innovations in military weapons and tactics since circa the Civil War are ascribed to Americans, or at least Anglo-Saxons, as if the author was schooled in late Stalin’s Russia, where all technical or exploration achievements ought to be backdated to Russian protagonists. The purpose of this book is to justify apparently insatiable appetite of the Pentagon, after the Cold War, to procure new and expensive weapons systems without any consideration for their tactical suitability or sound technical design, on the basis of pure “gut feeling” by the military bureaucrats.

Thursday, November 29, 2007

Response to an English friend on the question: “What is Putin up to now?” The letter was composed in Nov. 2007 and may not reflect later events

Response to an English friend on the question: “What is Putin up to now?” The letter composed in Nov. 2007

US State Department at any given time has only one template for installing pliable governments, a.k.a. puppets. Between 1910s and 1970s this template was to pay the generals to change the government of some Latin American or Asian country they decided to bless in this way.

If you want to read the entire essay, please, follow the link to the comment #1

US State Department at any given time has only one template for installing pliable governments, a.k.a. puppets. Between 1910s and 1970s this template was to pay the generals to change the government of some Latin American or Asian country they decided to bless in this way.

If you want to read the entire essay, please, follow the link to the comment #1

Wednesday, November 21, 2007

Mark Mendeles, Military Transformations: past and present. Historical lessons for the 21st century, Praeger Security, Westport, 2007.

ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99190-6

Author asserts that military organizations are intrinsically conservative and process- rather than results-oriented and that all innovation comes from “military mavericks” acting on suggestions from academic pundits. Very well may be, but is unrestrained innovation always positive? Speer’s tenure at the Nazi Ministry of Armaments, Ogarkov-Ustinov tandem in USSR between 1976 and 1985 and Ramsfeld’s stewardship of the DoD shows that too much of effected change can be quite disastrous. Despite all differences in the above three situations, all were characterized by multiplication of ultra-modern, for the times, and ultra-expensive and resource-intensive weapon systems, which were too unreliable, did not fit into tactical planning or could not be produced in sufficient quantities to produce desired influence on the outcome of the conflict.

My verdict: clever, but unconvincing defense of Ramsfeldianism.

Author asserts that military organizations are intrinsically conservative and process- rather than results-oriented and that all innovation comes from “military mavericks” acting on suggestions from academic pundits. Very well may be, but is unrestrained innovation always positive? Speer’s tenure at the Nazi Ministry of Armaments, Ogarkov-Ustinov tandem in USSR between 1976 and 1985 and Ramsfeld’s stewardship of the DoD shows that too much of effected change can be quite disastrous. Despite all differences in the above three situations, all were characterized by multiplication of ultra-modern, for the times, and ultra-expensive and resource-intensive weapon systems, which were too unreliable, did not fit into tactical planning or could not be produced in sufficient quantities to produce desired influence on the outcome of the conflict.

My verdict: clever, but unconvincing defense of Ramsfeldianism.

Thursday, November 15, 2007

Susan L. Shirk, China: fragile superpower, Oxford University Press, 2007.

This is the only English-language analysis of the US-China relations in connection with the Chinese internal politics, which is not written in “anthropomorphic” terms—states as actors with coherent character and traits, personified by their leaders—typical for Anglo-Saxon political science. Her analysis is very interesting but proposals are pedestrian and do not go much beyond lecturing Chinese leaders on the advantages of Anglo-Saxon style democracy, a rotten lesson after the “Bush doctrine.”

Friday, November 2, 2007

Cesium scare

When the firemen become too numerous, they take to arson.

Oriental proverb

When we created a $50 bn. plus a year, 200,000-staff monster called Department of Internal Security, it was clear to everybody who has any understanding how bureaucracy works that they would work tirelessly to expand their sphere of competence. One of the well-treaded methods is to circulate sensational new threat, usually through a strategically corrupted Brit, then let Government officials to ward off angry questions by the media and the Congress when they do something about it until public hysteria reaches such proportions that they will be “compelled” to take resolute and very expensive action. Works every time. Worked for Bush Sr. and Kuwait (“babies thrown onto the bayonets”), Clinton in Kosovo (still remember “stopping the genocide?”), Bush in Iraq (“mushroom cloud in 45 minutes”); Iran (another mushroom cloud) and Sudan (another genocide) are the cases still pending.

Now new threat, namely Cs-137 in medical devices is posed to take over public imagination. This isotope of cesium is typically used as a salt crystal(s) packed into hard ceramic pellet. By itself, Cs-137 (half-life 30.2 years) decays through a normal β-channel. Its medical use is based on the by-product of the decay: a metastable isotope Ba-137 (half-life 2.6 sec.), which emits energetic γ-radiation. Collimated, this radiation kills tumors.

Dr. Zimmerman, Professor of King’s College in London, a well-known national security guru suggested in his op-ed piece in “New York Times” that the malefactors using only the isotopes in available medical radiation devices can contaminate pretty much the entire United States. Though, Zimmerman is a highly educated expert, my single personal contact with him suggested of someone capable of rush and unfounded judgments. Lately, he seem to have lost his mental stability completely over the polonium poisoning accident in London, inserting his ramblings about it in everything he writes or talks about.

Metallic cesium is highly reactive (can conflagrate in open air) and technically applied chloride CsCl is well-soluble in water. These properties are in sharp contrast to, e.g. uranium and plutonium and their oxides, which are rather neutral and can exist in the environment in the form of dust for millennia. High reactivity of cesium means, for one, that rain provides a fair degree of decontamination. Stuff going through rivers into water treatment plants is likely to be immobilized in mud, again due to the extreme ease, with which Cs as all other alkali metals form stable salts. Its relatively short half-life (30 yrs. vs. 24,000 years for Pu) makes contamination of the ground water table a remote threat.

Of course, Cs-137 is a highly dangerous substance if ingested or inhaled. Dismantling of sources containing radioactive isotopes must be performed by trained and competent personnel and not by every London-based fugitive from the Russian justice or junkyard bum hunting for the rare metals. I would abstain from using even ordinary cesium chloride as a dietary replacement for table salt: diarrhea and vomiting may ensue. But it is not lethal in practical quantities as suggested by Zimmerman, unless you are force-fed by it through enema somewhere at Abu Ghraib. Yet, because of the same solubility issue and affinity to natural salt, simple increase of water intake already provides a workable method to mitigate exposure, before professional help becomes available. In the case of attack by the Cs bomb, I would recommend drinking enough water and not to consume unknown substances, picked from the ground or technical devices, nor use them as components for body washes and paints. And do not wallow in the mud naked.

Oriental proverb

When we created a $50 bn. plus a year, 200,000-staff monster called Department of Internal Security, it was clear to everybody who has any understanding how bureaucracy works that they would work tirelessly to expand their sphere of competence. One of the well-treaded methods is to circulate sensational new threat, usually through a strategically corrupted Brit, then let Government officials to ward off angry questions by the media and the Congress when they do something about it until public hysteria reaches such proportions that they will be “compelled” to take resolute and very expensive action. Works every time. Worked for Bush Sr. and Kuwait (“babies thrown onto the bayonets”), Clinton in Kosovo (still remember “stopping the genocide?”), Bush in Iraq (“mushroom cloud in 45 minutes”); Iran (another mushroom cloud) and Sudan (another genocide) are the cases still pending.

Now new threat, namely Cs-137 in medical devices is posed to take over public imagination. This isotope of cesium is typically used as a salt crystal(s) packed into hard ceramic pellet. By itself, Cs-137 (half-life 30.2 years) decays through a normal β-channel. Its medical use is based on the by-product of the decay: a metastable isotope Ba-137 (half-life 2.6 sec.), which emits energetic γ-radiation. Collimated, this radiation kills tumors.

Dr. Zimmerman, Professor of King’s College in London, a well-known national security guru suggested in his op-ed piece in “New York Times” that the malefactors using only the isotopes in available medical radiation devices can contaminate pretty much the entire United States. Though, Zimmerman is a highly educated expert, my single personal contact with him suggested of someone capable of rush and unfounded judgments. Lately, he seem to have lost his mental stability completely over the polonium poisoning accident in London, inserting his ramblings about it in everything he writes or talks about.

Metallic cesium is highly reactive (can conflagrate in open air) and technically applied chloride CsCl is well-soluble in water. These properties are in sharp contrast to, e.g. uranium and plutonium and their oxides, which are rather neutral and can exist in the environment in the form of dust for millennia. High reactivity of cesium means, for one, that rain provides a fair degree of decontamination. Stuff going through rivers into water treatment plants is likely to be immobilized in mud, again due to the extreme ease, with which Cs as all other alkali metals form stable salts. Its relatively short half-life (30 yrs. vs. 24,000 years for Pu) makes contamination of the ground water table a remote threat.

Of course, Cs-137 is a highly dangerous substance if ingested or inhaled. Dismantling of sources containing radioactive isotopes must be performed by trained and competent personnel and not by every London-based fugitive from the Russian justice or junkyard bum hunting for the rare metals. I would abstain from using even ordinary cesium chloride as a dietary replacement for table salt: diarrhea and vomiting may ensue. But it is not lethal in practical quantities as suggested by Zimmerman, unless you are force-fed by it through enema somewhere at Abu Ghraib. Yet, because of the same solubility issue and affinity to natural salt, simple increase of water intake already provides a workable method to mitigate exposure, before professional help becomes available. In the case of attack by the Cs bomb, I would recommend drinking enough water and not to consume unknown substances, picked from the ground or technical devices, nor use them as components for body washes and paints. And do not wallow in the mud naked.

Thursday, October 11, 2007

W. Langewiesche, The atomic bazaar: the rise of atomic poor

W. Langewiesche, The atomic bazaar: the rise of atomic poor, Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2007, ISBN 0-374-10678-2

Throughout the 90s, “The New York Times” and WSJ entertained their readers by stories that in Russia one can buy nuclear bombs on the flea markets and that generally, the Russians are the source of all evil on this planet. By the new millennium the readers of respectable newspapers got bored and the torch was passed to others, such as this “Vanity Fair” columnist. His interviews with unnamed “experts” contain such technical absurdities and his description of Russian nuclear facility is so generic a picture of a provincial Russian town in the Western press that I have little doubt that his main (if not the only) interlocutors were drug-addled members of the Moscow press core and their prostitute friends. Or he could have lifted the descriptions from tabloid web sites sitting pretty in his upscale NYC or LA condo.

To be completely fair I must remind the reader that the only WMD arsenal which leaked was the US biological weapons research complex. This resulted in the “anthrax scare” and the death of one tabloid journalist.

Throughout the 90s, “The New York Times” and WSJ entertained their readers by stories that in Russia one can buy nuclear bombs on the flea markets and that generally, the Russians are the source of all evil on this planet. By the new millennium the readers of respectable newspapers got bored and the torch was passed to others, such as this “Vanity Fair” columnist. His interviews with unnamed “experts” contain such technical absurdities and his description of Russian nuclear facility is so generic a picture of a provincial Russian town in the Western press that I have little doubt that his main (if not the only) interlocutors were drug-addled members of the Moscow press core and their prostitute friends. Or he could have lifted the descriptions from tabloid web sites sitting pretty in his upscale NYC or LA condo.

To be completely fair I must remind the reader that the only WMD arsenal which leaked was the US biological weapons research complex. This resulted in the “anthrax scare” and the death of one tabloid journalist.

Victoria Finlay, Jewels: A Secret History

Victoria Finlay, Jewels: A Secret History, Ballantine Books, NY 2006.

ISBN-10: 0-345-46694-2

Amusing travelogue. Wittily organized according to Mohs hardness scale of jewels (which are not necessarily minerals: amber, pearl, jet and opal all involve organic processes in their formation). Discussion of artificial corundum gemstones— ruby, sapphire— is outdated and superficial: the requirements of laser technology caused production of synthetic rubies of arbitrary size, etc. Industrial applications of diamonds are also missing. To a pity, like the Nazi Germany, in which no printed material could come out without anti-Semitic rants no matter how tangential to the subject, these days any piece written by the Britisher must contain racialist abuse of the Russians (Chapter “Amber”).

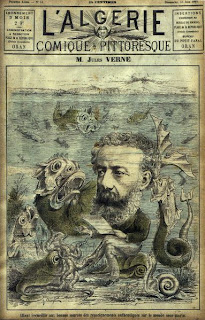

William Butcher, Jules Verne. The Definitive Biography

William Butcher, Jules Verne. The Definitive Biography. Thunder’s mouth press, NY 2006

ISBN-10: 1-56025-854-3

The author calls it “a definitive biography.” There is nothing definitive in it, except for meticulous reconstruction of Verne’s home addresses throughout his life, financial affairs—containing unfounded allegations of Hetzel of cheating the author—, and lugubrious allegations of Verne’s homosexuality. The analysis of his books is substituted by brief retelling of the plots, the inquest into science and technology in his stories is perfunctory. There is precious little in this biography concerning Verne’s political beliefs and social attitudes apart from conventional platitudes describing a run-of-the-mill upper middle class Victorian gentleman, which indeed he was.

Most interesting part of the book deals with his childhood and youth. The author put a significant effort to reconstruct Jules Verne’s own travels. But these are entirely mundane given his station as a modestly wealthy Victorian. The author rejects the “prophetic” quality of his work. Forget his 1960s world divided between US and Russia, Americanized Western Europe ruled by unprincipled media magnates, in which people travel in gas-powered vehicles, US lunar module fished out of the Pacific by the Navy ship and one of the last, non-fiction, novels dealing with ethnic tensions in Latvia! Forget raising a question of moral responsibility of the scientist for the fate of his invention, etc. etc.

The author raises a well-researched issue of the literary quality of his writing. Good, but that’s was not what his novels were famous for, in his lifetime and thereafter, especially in bad English translations. Call, charitably, modern world outlook “realism,” but also “universal cynicism.” Jules Verne personified, for the later generations, the mid-to-late XIX century world view with its unbounded optimism in technical and moral improvement of humanity, which our times are sorely lacking. His books were stories of vision and perseverance and still are.

Friday, August 24, 2007

Josef Joffe, Überpower: The Imperial Temptation of America

Josef Joffe, Überpower: The Imperial Temptation of America. W. W. Norton, NY, ISBN-10: 0393330141

Josef Joffe is a pro-American German conservative, so when American media wants to have an opinion on German affairs, he is “Germany.” For instance, before the election of Social Democratic majority in 1998 and subsequent re-election, which were obvious from all opinion polls, American media discussed the upcoming victory of conservatives largely because of JJ’s opposite opinion, despite of the fact that his stance was a pure partisan propaganda. He is a smart man, unlike our conservatives, so I do not think for a second that he really believed it.

In his new book, The Überpower, Josef Joffe also says what neoconservatives want to hear: namely, that with enough persistence, things would go well for them. He implores them just to have patience and all their thorny debacles will turn roses—I remind you that collection of roses from the streets of Baghdad was considered by the neocons a major remaining task for American Army― after the American liberation.

His thinking is based entirely on historic and pseudo-historic analogies. But politics is so interesting precisely because historical analogies do not always work. As most European cons, he is entirely oblivious to the economic and electoral part of the equation. American neoconservatives cannot persist not because they don’t want to, but because whatever relics of electoral process we still have in this country, would not allow them to continue unabated.

Yes, Chinese music or Russian films are not so popular in the world as American hip-hop or Hollywood movies, but does it transpire into the soft power of the United States as Joffe tends to present it? Paraphrasing one line of thought of Schumpeter, originally developed for internal struggles in the feudal Europe, the country which achieves economic and military dominance usually has its political and cultural institutions to be admired and imitated, not the other way around. Spain became a preeminent world power in XVI century from a European backwater, and all courts started to follow Spanish court rituals. France of the Sun King replaced Spain in the second half of the XVII century and French music and theater became the model for the rest of Europe. On the contrary, decline of Germany after the First World War and the Nazi rise to power, gave the status of then world-famous German universities a blow, from which they have yet to recover. Early XX century America, which was an economic powerhouse but a distant scientific province, established its scientific predominance as a result of mass exodus of European scientists and huge funding during the World War II, which turned the US universities from the academic backwater into the marvel of the world.

His economic calculations “proving” that Chinese economy will never be in the same ballpark as the American smacks of peculiarly German disregard of a common sense when the normative thinking is involved. For instance, he cites current Chinese GDP per capita as $1,100. Even if he never visited China, just looking at the Shanghai skyline on TV, can he argue that people there have one-eighth of a living standard of an average Mexican, or one-thirteenth of an average Czech? Yet, this is what is implied by Joffe’s “economic” calculations.

Continuing economic and political rise of China and India will certainly have major repercussions for their soft-power status as well. There is of course never a sheer determinacy. For instance, Japan has such an aversion to immigration, idiosyncratic culture and disdain for foreign sensitivities that even in the countries, where Japanese culture is admired and imitated, the real Japanese are hated. American politicians would love to have an empire, but American taxpayers would not pay a dime for it. Every time there is a big foreign policy issue confronting a parochial concern of an obscure legislator from the Carolinas or Louisiana, Louisiana invariably wins. German taxpayers would cash in for greatness; but the peculiar German habit of bossing everyone in their wake made Germans detested even in the countries of Eastern Europe, which are otherwise totally dependent on the German economy.

One of the examples of pseudo-historical thinking on a part of JJ: “The historical Sino-Russian rivalry will continue as far as the eyes can see.” Does it ever occur to him that political rivalries between states are the results of the conflict of real interests? Russian and Chinese Empires coexisted quite well since their historical meeting in XVII century. Big falling out between PRC and USSR, which, by the way, JJ can never distinguish from Russia, happened only once in the 1960s. The reason for it was quite transparent: two largest Communist powers struggled for the leadership in the Communist movement, and by proxy of the Third World. Currently, the foreign policies of these two nations are as devoid of ideology, as they ever can be: where is the reason for conflict? Russia feels threatened by the US and its European supplicants; China wants to regain Taiwan and to build its backyard in the South-East Asia. Both fear the resurgence of the Islamic fundamentalists in the Central Asia. Their foreign policy goals are rather complementary.

Josef Joffe mentions Europe mostly as a whole, again on pure geographic grounds. Yet, there is an obvious fissure between old continental powers: Germany, France, Italy, Spain and the UK-Nordic bloc, which largely follows American foreign policy priorities. Both centers of power are currently involved in fierce competition for the Eastern Europe, with the Poland, Bulgaria, Balkan states and the Baltics gravitating towards Anglo-American alliance and Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary—towards the continentals. Romania, as always, stays in the middle. Anglo-Saxon-Nordic group shares militaristic foreign policies, ethnocratic domestic tendencies and anti-Russian vitriol. Their policies towards EU are to dilute its supra-national component and to tie up its common foreign policy to the American-dominated NATO.

The continental group is lukewarm towards exercise of military power or even substantial military buildup, preserves the welfare state, insists on supra-national functions and majority rule in the EU and, generally prefers accommodation of and economic cooperation with Russia. One can project a split along these lines, with equal ease, as a potential evolution of the EU into United States of Europe with truly common foreign policy.

The book of Josef Joffe is certainly more intellectually sound than the treatises of American conservatives, who are totally divorced from reality. I would heartily recommend it for a discussion in a high school class or an undergraduate program in International Relations. However, its value as a policy guide is nil. His thinking is dominated by the demands of the lucrative American lecture circuit and not in the slightest by his sincere desire to work out the solutions for the world’s problems.

Josef Joffe is a pro-American German conservative, so when American media wants to have an opinion on German affairs, he is “Germany.” For instance, before the election of Social Democratic majority in 1998 and subsequent re-election, which were obvious from all opinion polls, American media discussed the upcoming victory of conservatives largely because of JJ’s opposite opinion, despite of the fact that his stance was a pure partisan propaganda. He is a smart man, unlike our conservatives, so I do not think for a second that he really believed it.

In his new book, The Überpower, Josef Joffe also says what neoconservatives want to hear: namely, that with enough persistence, things would go well for them. He implores them just to have patience and all their thorny debacles will turn roses—I remind you that collection of roses from the streets of Baghdad was considered by the neocons a major remaining task for American Army― after the American liberation.

His thinking is based entirely on historic and pseudo-historic analogies. But politics is so interesting precisely because historical analogies do not always work. As most European cons, he is entirely oblivious to the economic and electoral part of the equation. American neoconservatives cannot persist not because they don’t want to, but because whatever relics of electoral process we still have in this country, would not allow them to continue unabated.

Yes, Chinese music or Russian films are not so popular in the world as American hip-hop or Hollywood movies, but does it transpire into the soft power of the United States as Joffe tends to present it? Paraphrasing one line of thought of Schumpeter, originally developed for internal struggles in the feudal Europe, the country which achieves economic and military dominance usually has its political and cultural institutions to be admired and imitated, not the other way around. Spain became a preeminent world power in XVI century from a European backwater, and all courts started to follow Spanish court rituals. France of the Sun King replaced Spain in the second half of the XVII century and French music and theater became the model for the rest of Europe. On the contrary, decline of Germany after the First World War and the Nazi rise to power, gave the status of then world-famous German universities a blow, from which they have yet to recover. Early XX century America, which was an economic powerhouse but a distant scientific province, established its scientific predominance as a result of mass exodus of European scientists and huge funding during the World War II, which turned the US universities from the academic backwater into the marvel of the world.

His economic calculations “proving” that Chinese economy will never be in the same ballpark as the American smacks of peculiarly German disregard of a common sense when the normative thinking is involved. For instance, he cites current Chinese GDP per capita as $1,100. Even if he never visited China, just looking at the Shanghai skyline on TV, can he argue that people there have one-eighth of a living standard of an average Mexican, or one-thirteenth of an average Czech? Yet, this is what is implied by Joffe’s “economic” calculations.

Continuing economic and political rise of China and India will certainly have major repercussions for their soft-power status as well. There is of course never a sheer determinacy. For instance, Japan has such an aversion to immigration, idiosyncratic culture and disdain for foreign sensitivities that even in the countries, where Japanese culture is admired and imitated, the real Japanese are hated. American politicians would love to have an empire, but American taxpayers would not pay a dime for it. Every time there is a big foreign policy issue confronting a parochial concern of an obscure legislator from the Carolinas or Louisiana, Louisiana invariably wins. German taxpayers would cash in for greatness; but the peculiar German habit of bossing everyone in their wake made Germans detested even in the countries of Eastern Europe, which are otherwise totally dependent on the German economy.

One of the examples of pseudo-historical thinking on a part of JJ: “The historical Sino-Russian rivalry will continue as far as the eyes can see.” Does it ever occur to him that political rivalries between states are the results of the conflict of real interests? Russian and Chinese Empires coexisted quite well since their historical meeting in XVII century. Big falling out between PRC and USSR, which, by the way, JJ can never distinguish from Russia, happened only once in the 1960s. The reason for it was quite transparent: two largest Communist powers struggled for the leadership in the Communist movement, and by proxy of the Third World. Currently, the foreign policies of these two nations are as devoid of ideology, as they ever can be: where is the reason for conflict? Russia feels threatened by the US and its European supplicants; China wants to regain Taiwan and to build its backyard in the South-East Asia. Both fear the resurgence of the Islamic fundamentalists in the Central Asia. Their foreign policy goals are rather complementary.

Josef Joffe mentions Europe mostly as a whole, again on pure geographic grounds. Yet, there is an obvious fissure between old continental powers: Germany, France, Italy, Spain and the UK-Nordic bloc, which largely follows American foreign policy priorities. Both centers of power are currently involved in fierce competition for the Eastern Europe, with the Poland, Bulgaria, Balkan states and the Baltics gravitating towards Anglo-American alliance and Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary—towards the continentals. Romania, as always, stays in the middle. Anglo-Saxon-Nordic group shares militaristic foreign policies, ethnocratic domestic tendencies and anti-Russian vitriol. Their policies towards EU are to dilute its supra-national component and to tie up its common foreign policy to the American-dominated NATO.

The continental group is lukewarm towards exercise of military power or even substantial military buildup, preserves the welfare state, insists on supra-national functions and majority rule in the EU and, generally prefers accommodation of and economic cooperation with Russia. One can project a split along these lines, with equal ease, as a potential evolution of the EU into United States of Europe with truly common foreign policy.

The book of Josef Joffe is certainly more intellectually sound than the treatises of American conservatives, who are totally divorced from reality. I would heartily recommend it for a discussion in a high school class or an undergraduate program in International Relations. However, its value as a policy guide is nil. His thinking is dominated by the demands of the lucrative American lecture circuit and not in the slightest by his sincere desire to work out the solutions for the world’s problems.

Friday, June 22, 2007

Control over weapons in outer space

Control over the weapons in outer space

“…Your editorial is mostly an opinion, not a well-demonstrated case study… The US is not the only one contemplating such a move [i.e. the offensive weapons in space—A. B.]. Our military and society now depend on satellites, and we can ill afford a “space Pearl Harbor.” Finally, monitoring any satellite militarization is extremely difficult.”

From the letter to “Scientific American”, 12/2005 by Alan Bertaux

A usual argument of the philosophical opponents of the arms control is that a given kind of weapons is impossible to verify. Typically, this is a deliberate falsehood; for instance, the opponents of control over the biological weapons were stumbling over the USSR’s opposition to the random on-site inspections. However, after USSR collapsed and all inspection protocols were agreed upon, in mid-90s, American opponents of the BWT derailed it by insisting on the immunity of most US biological production facilities and research centers from inspections. Yet, in 1990s, unlike the 1960s, the US Senate had much less common sense. Then it dismissed Teller’s suggestions that the Test Ban Treaty was impossible to verify, because USSR can conduct nuclear tests undetectably on the far side of the Moon, or behind the Sun, in another version.

This falsehood is perpetuated with respect to the weapons in the outer space on the same grounds of verification impossibility. While, one must recognize that no particular verification system is fool-proof, one, as this was the case with Iraq’s WMDs, can achieve practical degree of assurance where undetected violations are either insignificant or will be detected before they come to deployment of any practical weapons system.

Control over the space assets is greatly aided by the fact, that the number of space launching sites is very limited, much more so than, e.g. the number of nuclear reactors, and all launches are reliably detected by the modern radar and optical technology. Even in the future, when private spaceports may appear, their licensing can be made contingent on compliance with basic universal rules. Then, combination of on-site monitoring teams, prohibition to scramble launching telemetry and randomized inspections can be successfully used for detecting non-compliance with a treaty.

Another issue, frequently appearing with respect to the space weapons is the difficulty to distinguish a space vehicle with or without offensive weapons or offensive weapons components on board. This is hard, though not improbable in space (see below), yet on Earth, the inspectors can rely on the number of obvious clues and the proverbial learning curve: intelligent human inspectors quickly learn where to look for violations. The suspicious signatures may include:

• Excessive size or weight of the satellite with respect to a declared mission;

• The elements of maneuverability inconsistent with a declared mission;

• Presence of sensors inconsistent with a mission;

• Energy consumption requirements or the size of energy sources far in excess that is usually demanded for a similar mission;

• Undeclared or unexplained devices and assemblies on board;

• Installation of certain inherently suspect devices, such as high-powered lasers or microwave emitters;

• Armoring of the satellite or the elements of stealth.

Some of the space vehicles can legitimately emit nuclear radiation because of the isotope power sources or nuclear reactors on board. Yet, modern sensors partly developed as a response to cross-border terrorism, can detect the emission spectrum or internal placement of fissionable material with enough accuracy to exclude the presence of the nuclear weapons on board.

The potential cheaters could claim that they are not as sophisticated as their opponents in miniaturization of components, or in reducing energy consumption of legitimate on-board equipment. However, as is the case with all detective work, this is the compound weight of the clues, which creates a conviction of violation. If negotiated protocols are sensible, the satellites left “in strong suspicion” by the on-site commissions, can be also launched, but it would effectuate a more stringent monitoring regimen vis-à-vis suspect objects. Also, in negotiating a treaty, leading space powers can impose the restrictions on the ability to service and retrieve suspect satellites while in orbit.

The on-the-orbit monitoring can include compliance of the parameters of the orbit with the declared mission, independent control over the maneuvers of the space vehicle, independent or collective monitoring of the electromagnetic emissions from the satellite (frequency range, energy, time characteristics). Further development of infrared technology can allow independent monitoring of the heat balance of the satellite and, hence, verify its energy consumption. Finally, a flag-raising event may be an ability of a satellite to fly in formations.

None of the proposed measures compromise military satellites with legitimate non-offensive functions, such as optical and electronic reconnaissance, radar or lidar monitoring, global positioning, communications and early warning. All their military secrets will be safely hidden in the software on their microchips. Because the functioning of US civilian economy and armed forces relies on the satellites more than any other nation, physical and informational security of these satellites is much more important than the elusive goals of threatening Earth from space.

“…Your editorial is mostly an opinion, not a well-demonstrated case study… The US is not the only one contemplating such a move [i.e. the offensive weapons in space—A. B.]. Our military and society now depend on satellites, and we can ill afford a “space Pearl Harbor.” Finally, monitoring any satellite militarization is extremely difficult.”

From the letter to “Scientific American”, 12/2005 by Alan Bertaux

A usual argument of the philosophical opponents of the arms control is that a given kind of weapons is impossible to verify. Typically, this is a deliberate falsehood; for instance, the opponents of control over the biological weapons were stumbling over the USSR’s opposition to the random on-site inspections. However, after USSR collapsed and all inspection protocols were agreed upon, in mid-90s, American opponents of the BWT derailed it by insisting on the immunity of most US biological production facilities and research centers from inspections. Yet, in 1990s, unlike the 1960s, the US Senate had much less common sense. Then it dismissed Teller’s suggestions that the Test Ban Treaty was impossible to verify, because USSR can conduct nuclear tests undetectably on the far side of the Moon, or behind the Sun, in another version.

This falsehood is perpetuated with respect to the weapons in the outer space on the same grounds of verification impossibility. While, one must recognize that no particular verification system is fool-proof, one, as this was the case with Iraq’s WMDs, can achieve practical degree of assurance where undetected violations are either insignificant or will be detected before they come to deployment of any practical weapons system.

Control over the space assets is greatly aided by the fact, that the number of space launching sites is very limited, much more so than, e.g. the number of nuclear reactors, and all launches are reliably detected by the modern radar and optical technology. Even in the future, when private spaceports may appear, their licensing can be made contingent on compliance with basic universal rules. Then, combination of on-site monitoring teams, prohibition to scramble launching telemetry and randomized inspections can be successfully used for detecting non-compliance with a treaty.

Another issue, frequently appearing with respect to the space weapons is the difficulty to distinguish a space vehicle with or without offensive weapons or offensive weapons components on board. This is hard, though not improbable in space (see below), yet on Earth, the inspectors can rely on the number of obvious clues and the proverbial learning curve: intelligent human inspectors quickly learn where to look for violations. The suspicious signatures may include:

• Excessive size or weight of the satellite with respect to a declared mission;

• The elements of maneuverability inconsistent with a declared mission;

• Presence of sensors inconsistent with a mission;

• Energy consumption requirements or the size of energy sources far in excess that is usually demanded for a similar mission;

• Undeclared or unexplained devices and assemblies on board;

• Installation of certain inherently suspect devices, such as high-powered lasers or microwave emitters;

• Armoring of the satellite or the elements of stealth.

Some of the space vehicles can legitimately emit nuclear radiation because of the isotope power sources or nuclear reactors on board. Yet, modern sensors partly developed as a response to cross-border terrorism, can detect the emission spectrum or internal placement of fissionable material with enough accuracy to exclude the presence of the nuclear weapons on board.

The potential cheaters could claim that they are not as sophisticated as their opponents in miniaturization of components, or in reducing energy consumption of legitimate on-board equipment. However, as is the case with all detective work, this is the compound weight of the clues, which creates a conviction of violation. If negotiated protocols are sensible, the satellites left “in strong suspicion” by the on-site commissions, can be also launched, but it would effectuate a more stringent monitoring regimen vis-à-vis suspect objects. Also, in negotiating a treaty, leading space powers can impose the restrictions on the ability to service and retrieve suspect satellites while in orbit.

The on-the-orbit monitoring can include compliance of the parameters of the orbit with the declared mission, independent control over the maneuvers of the space vehicle, independent or collective monitoring of the electromagnetic emissions from the satellite (frequency range, energy, time characteristics). Further development of infrared technology can allow independent monitoring of the heat balance of the satellite and, hence, verify its energy consumption. Finally, a flag-raising event may be an ability of a satellite to fly in formations.

None of the proposed measures compromise military satellites with legitimate non-offensive functions, such as optical and electronic reconnaissance, radar or lidar monitoring, global positioning, communications and early warning. All their military secrets will be safely hidden in the software on their microchips. Because the functioning of US civilian economy and armed forces relies on the satellites more than any other nation, physical and informational security of these satellites is much more important than the elusive goals of threatening Earth from space.

Sunday, May 27, 2007

Moshe Lewin, The Soviet Century

Moshe Lewin, The Soviet Century, Verso, London, 2005

ISBN-10: 1-84467-016-3

Very nuanced, but totally wrong-headed book on the Soviet system of Government. In particular, the author for the first time uses the numerical data on the size of CPSU apparatus and its cost from recently declassified archival sources. The description of society and government under Stalin is brilliant, but his general ideas about Soviet era are borrowed from revisionist school (S. Cohen, J. Hough, etc.) and are complete trash. For instance, in accordance with Soviet-era textbooks and American revisionist historians he describes pre-revolutionary Russia as a barbaric semi-medieval nation. These perceptions were deliberately cultivated by the Soviet propaganda as to justify the violence of the Bolshevik coup and low living standards in the USSR. In fact, just before the World War I, Russian Empire edged Austro-Hungary as a fifth leading industrial power of the world after the USA, Germany, Great Britain and France.

The author seems to adhere to a strange theory, in which Soviet Party-State was replaced in the 1960s by the domination of the technical bureaucracy of the Council of Ministers. The whole idea of the struggle for the primacy of the two competing hierarchies: that of the Central Committee and the Council of Ministers is a pure concoction of the revisionist school and has no particular factual basis. The relationships between the Central Committee and the Council of Ministers could be obscured at times, because several important ministers (Foreign Affairs, Defense, State Security, Heavy Industries and Internal Affairs) at times also held high ranks in Party hierarchy. However, the primacy of the Party apparatus was never much in question from the early 1920s to the time of disintegration of the Soviet Union.

Yet, for all its shortcomings, this book provides the most sophisticated depiction of the inner workings of the Soviet system of government, which has been so far available in English.

Sunday, May 20, 2007

Civil Wars

Civil wars

Alex S. Bliokh

Once walking through the halls of Los Alamos I noticed a photograph which was not known to me but which style and subject was painstakingly familiar to me through school textbooks and onwards: Russian Civil War. However, coming closer I spotted some differences in uniform and read the title indicating that these were Carranzistas in Revolutionary Mexico. This was a good opportunity to enter the office and ask its owner, a well-known scientist of Mexican extraction about the photograph and what else. “What were the reasons for the civil war? As always”- responded he- “an unresolved agrarian question.”

Much later I stumbled upon the observation by Amartya Sen (Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics, 1998) who lived through the post-Independence hunger in Punjab that the starting point of his exploration was the realization that democracies rarely if ever had known starvation. I started to recollect until I could formulate another observation, which was equally improbable but wholly supported by empirical count, namely, that there was not a single civil war in an industrialized nation. On the contrary, civil wars frequently accompanied the triumph of industrial economic order over agrarian civilization, for instance, in the United States. Medical records of the American Civil War indicated that more than 85% of the soldiers indicated their social position as farmer or a farm hand. What then to speak of 1918 Russia, 1920 Mexico, or Central America, any time, any place.

Civil wars always seem to be magically attached to stubborn resistance or revolt of peasants against somebody: their masters the landlords, an occupying power, emerging urbanized and/or industrial agendas of the ruling elite, etc. etc. The only example of civil war, which can be remotely ascribed to urban political culture and interests would be civil war in Ireland (1922-1923) of which I (and most Europeans) know very little. However, Eire at that time was hardly an industrial nation and one can be sure, that bodies of peasant stock were largely responsible for manning troops and falling on both sides.

Third observation has to do with the particular ferocity of the peasant war. Nazi Germany seems to be the unique XX Century case in which urban society and government displayed propensity for genocide.[1] My explanation is that the genocide was an original form of warfare. Subsistence societies simply annihilated opposing tribes, or at least their male part. Preservation of female part as (sex) slaves also made direct sense for the small groups suffering from chronic inbreeding.

There seem to be many non-biologic, economic reasons for connection of warfare and land ownership, pointing in the same direction. First, the war brings only ruin and hardships for the majority of urban dwellers for them to start it on their own accord. On the contrary, for centuries, agrarian civilizations were attuned to co-existence with almost permanent warfare. Peasant going to war could either conquer more land or pastures in the foreign land or perish, in which case, his extended family would re-divide his plot at home. Hard-pressed burgher will likely prefer to pack and leave in search for the better. Not so a peasant, or a landlord. They can neither move their main asset, nor be separated from it, and prosper.

This argument has nothing to do with class warfare. Both roundheads and ironsides of the Civil War in England represented landowning interests with different political outlook. Great peasant rebellions in XVI century Germany and Hungary, or XVII-XVIII century Russia were led by the minor knights, or by the soldiers of fortune, hardly a serf. Chin (Qin), the first dynasty, which united China, collapsed in a series of peasant rebellions, but the victorious faction was commanded by someone Liu Bang, a minor civil bureaucrat, who then became Emperor Gaozu, founder of the Han dynasty. Certainly, class oppression stoked these rebellions, but few, if any of them had amelioration of the lot of the oppressed as an important part of their program. Dynastic troubles, foreign domination or religious impiety of the ruling classes figured much more prominently in the revolutionary rhetoric. And peasant generals frequently installed themselves in palaces of the overthrown nobility and surrounded themselves with slave servants and concubines.

Second, the accumulation of capital for the development of urbanized society almost seems to require the robbing of some agrarian order, at home or/and abroad. Britain paved the way by mass removal of tenant peasants from the estates in the late XVI-XVII centuries and later supported its own industrializing economy by exploiting of agricultural communities from North America to the British Raj. When the US achieved independence from Britain, despite inheriting boundless continent, they fought a bloody civil war and imposed reconstruction on a recalcitrant agricultural South. Yet, from 1920s to 1950s United States de-facto colonized many economies of the South and Central America in service of their own industrial development.

Not all paths from agrarian to urban society were that straightforward. Spanish Empire exploited its American dependencies, and Spaniards financed accelerated urbanization and modernization, though not in Spain, but in the Low Countries. City-states of Northern Italy, the early European leader in capital formation, were unable to subjugate or maintain significant pockets of agricultural exploitation and by the end of XVII century fell far behind their Northern cousins. In Germany, it seems that the obverse took place: predominantly agricultural, but militaristic Prussia annexed to itself urbanized and industrialized areas, first, mining towns of Silesia in mid-XVIII century, then Baden, Saar and Rheinland in the course of XIX century Wars for Unification.

Late Medieval and early Modern France was convulsing in the series of Civil Wars more or less continuously from the beginning of XV to the mid-XVII century. But given the largely urban character of later political culture in France, civil war component became subdued in all French political upheavals of XVIII-XIX centuries. Vendee was only a side show of the French Revolution. And the revolutionary age in France has ended with violent suppression of the workers’ French Commune by largely peasant soldiery of the French Army in 1871[2], after which it peacefully dispersed to barracks and farms never to return as a factor in domestic political life.

In Russia, the tsarist regime was unable to solve a development dilemma before the First World War, in part because the ruling bureaucracy was reluctant to run roughshod over agricultural interests: the landowning class still, like in contemporary Prussia and Austria, remained a backbone of the Empire’s administrative and, especially, military apparatus. Moreover, the leading landowners-bureaucrats, like Stolypin, were rather timid in their assault on traditional peasantry as well, because they perceived the peasants and their parochial outlook as the counterweight to radicalized urban working classes and intelligentsia. Only Bolsheviks with their blatant disregard for human life, established order and economic rationality, could expropriate peasantry to build their own urbanized utopia on Russian soil.

I do not suggest here, as Marxist historians in the East and West were prone to do and some revisionists still assert, that there was anything rational or even preordained in the Soviet ruination of Russian peasant society. This means, rather trivially, that the extremely violent path taken by the Russian revolution had its roots in the previous contradictions of the Empire, which entered its industrial age with more than 80% of an agricultural population. Metaphorically speaking, traditional Russian peasantry was doomed to be despoiled on the eve of 30s. However, if the Imperial military were more capable and the tsarist bureaucracy more intellectually curious, it could go down in the throes of the Depression like Steinbeck’s Okies, rather than perish in the Bolshevik terror and Stalin’s collectivization.

One must not view this rather grim outlook of the peasant societies as condescending. They were the only form possible under the economic circumstances of the times. Food, which is necessary to consume every day, had limited possibility of storage and transportation far from production areas. The only method of sustenance for civilization, i.e. a tiny elite of militarized aristocracy, with accompanying priests, scribes, artisans and merchants who were serving predominantly the ruling clique, was to resort to periodic armed confiscations in the years of scarcity. One would be hard-pressed to stop war, or require builders of the temple, or makers of the weaponry to dissolve and fend for themselves just because of draught or other inopportune circumstance. The prospects for the new technologies in agriculture were scarce. Increased productivity in the conditions of primitive storage techniques, lengthy and uncertain transportation, could only cause drastic price reductions, wiping out the economic basis of communities, which would adopt them in the years of plenty. For the peasant commonwealth to withstand systematic armed depredations of their overlords and occasional—of the nomads—it had to be organized in large family-style units with mechanisms of mutual support[3] under strong patriarchal authority. This presumed expendability of the weaker members of the community, predominantly the women.

If my reasoning is true, what this may hold for the future? First, India and China, which still have a large sector of subsistence agriculture, may be equally able to dominate our century as to collapse in bloody civil wars. Second, African continent is doomed to the continuing cycles of civil wars despite all good will and economic aid, until (1) its economies including agricultural sector will be thoroughly industrialized and (2) African cities will be transformed in the direction of the Western, business-oriented model of urbanism.

In the present state of affairs African cities are the social extensions of rustic communities. Members of the same villages and tribes populate same residential neighborhoods and maintain traditional power structures in the industrial/service setting. From the American prospective, cities of many an African nation, and the famous “Arab street”, are the federations of “urban” gangs. Like the gangs in the West, they have nothing “urban” in origin. With their emphasis of ethnic/racial origin, loyalty to a long-gone, or invented communal ideals, a hierarchy based on force and submission to a core group of aggressive armed males and collective economic and sexual exploitation of women by the members of this group, they represent a transplant of traditional agrarian order into modern industrial and postindustrial economy. [4]

Appendix A.

French banileues, which became the hotbed of Paris riots of 2005, are also quasi-village communities unlike most American suburbia. In one of the ironies, many an American suburb, which is a village in the urban planning sense, does not possess any trace of a social life of village community. Deer and raccoons may come to property in abundance, and an occasional mountain lion or a bear, and houses are all made of wood; but one’s next door neighbor may be a Chinese, another—an Israeli, third—a Korean, others—Americans from all over the continent, but one does not know anything about them. They nod politely, or ask to pet a dog; that’s it. Personal contacts are centered on professional and school networks. Common religious affiliation, which was the reason for suburban segregation in the first place, plays little or no role. The neighborhood does not define, nor does it interfere in, intimate contacts, or marriage contracts.

On the contrary, French Moslem banileue is a village, despite an artificial look of a collection of grim high rise concrete housing projects. The loyalties are ethnocentric; North Africans may mix with Turks, Bosniaks or Albanians as partners in crime and rioting, but when the contact with the “white world” around ceases, the ethnic melee immediately reforms back into ethnic crystals.

Primary groups are formed around a fundamentalist imam as an extension of a village elder. Sister of a member who goes outside of the network for dating is defamed and severely punished. Former members of the community, who prospered socially and financially, are long gone and remember their former origins with a shudder, not too dissimilar to the residents of immigrant ghettoes of XX century America. Remaining are unemployed, semi-employed or work in a local economy; their professional position is neither a sort of identification, nor of a particular pride. Traditional villages probably had some internal hierarchy based on relative level of prosperity and/or strict or lax adherence to the morality norms[5] of the collective, but the nature of agricultural labor was common for them all and imposed an artificial uniformity on their already drab existence.

Appendix B

If the above reasoning is true, civil wars in Africa and in the Middle East cannot be reduced with economic aid. In fact, most disastrous civil wars happened in countries such as England (War of the Roses and Cromwell Revolution), United States (1861-1865), Argentina (large part of XIX century) and Russia (1918-1920), which were at the time major food producers and exporters and did not suffer from agricultural shortages per se. In some of the above cases abundance could have actually increased because of the reduced possibility to export surpluses.

I suggest that more important than providing aid would be to break down patriarchal structure. Only when a state ceases to be an extension of patrimony, there would be hope that people will find other ways to manage their conflicts than to engage in neighborly genocide. I am not a sociologist, even less of a demographer to propose a solution. One of the pillars of the traditional order is polygamy and the existence of extremely large families. In the society with subsistence agriculture keeping large families makes sense because the mortality is high and there is no social safety net. The only retirement package available to subsistence farmer is to be supported by one’s children. In the modern subsistence economies, which graduated to the Internet and Stingers, this makes no sense at all.

Creating an artificial shortage of women may be a one way to try. Short of Stalinist methods, this can be accomplished by encouraging women to emigrate from Africa, Middle East, Balkans and the Caucasus, but placing strict limits on the emigration of men. Then, if the creeping abolition of serfdom in the Western Europe in the wake of the Great Plague provides any guidance, the “price” of women in the society will rise until their professional skills will replace reproductive capacity as a main source of value. Once this happens and women convert their newfound economic power into political leverage, the likely result would be for them to curb the traditional power structure of male-centered urban chiefdom with its militant tendencies.

[1] Among poorly understood vagaries of the Nazi regime is the fixation of their leaders on the grabs of agricultural land, which they proposed to distribute to German colonists and to cultivate by the slave workforce of subjugated Slavs. Out of all totalitarian regimes, the modeling of the ruling class on the chivalric (i.e. land-owning) caste was also the most prominent in German Nazism. I did not find successful explanation to this strange, in the modern industrial state, obsession with agrarian utopianism. Yet all the Nazi leaders lived through the austerity of the first Weimar years.

[2] By most accounts, the bi-weekly suppression of the Paris Commune in 1871 cost more lives than all the terror of the French Revolution.

[3] For instance, this included different forms of open-field system under manorial organization.

[4] One might remember in that regard, that, that an early medieval lord of the manor himself had very limited resources to spend on his armed retinue. Most of their reward probably was contained in the possibility to live on his grounds and procure unlimited food and sex directly from his tenants.

[5] This “morality” ought not to be interpreted in Victorian terms. At one time or another, accepted practices included almost universal polygamy, ritual prostitution, castration, infanticide, parricide, cannibalism and necrophagia. Hellenistic “master of the house” could be, from a modern point of view, a violent pedophile and a whoremonger, but this did not impugn on his moral standing. On the contrary, inability to keep slaves and women of the house in their place, neglect of community affairs, or lack of cultural refinement could be a reason for severe reprobation.

Alex S. Bliokh

Once walking through the halls of Los Alamos I noticed a photograph which was not known to me but which style and subject was painstakingly familiar to me through school textbooks and onwards: Russian Civil War. However, coming closer I spotted some differences in uniform and read the title indicating that these were Carranzistas in Revolutionary Mexico. This was a good opportunity to enter the office and ask its owner, a well-known scientist of Mexican extraction about the photograph and what else. “What were the reasons for the civil war? As always”- responded he- “an unresolved agrarian question.”

Much later I stumbled upon the observation by Amartya Sen (Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics, 1998) who lived through the post-Independence hunger in Punjab that the starting point of his exploration was the realization that democracies rarely if ever had known starvation. I started to recollect until I could formulate another observation, which was equally improbable but wholly supported by empirical count, namely, that there was not a single civil war in an industrialized nation. On the contrary, civil wars frequently accompanied the triumph of industrial economic order over agrarian civilization, for instance, in the United States. Medical records of the American Civil War indicated that more than 85% of the soldiers indicated their social position as farmer or a farm hand. What then to speak of 1918 Russia, 1920 Mexico, or Central America, any time, any place.

Civil wars always seem to be magically attached to stubborn resistance or revolt of peasants against somebody: their masters the landlords, an occupying power, emerging urbanized and/or industrial agendas of the ruling elite, etc. etc. The only example of civil war, which can be remotely ascribed to urban political culture and interests would be civil war in Ireland (1922-1923) of which I (and most Europeans) know very little. However, Eire at that time was hardly an industrial nation and one can be sure, that bodies of peasant stock were largely responsible for manning troops and falling on both sides.

Third observation has to do with the particular ferocity of the peasant war. Nazi Germany seems to be the unique XX Century case in which urban society and government displayed propensity for genocide.[1] My explanation is that the genocide was an original form of warfare. Subsistence societies simply annihilated opposing tribes, or at least their male part. Preservation of female part as (sex) slaves also made direct sense for the small groups suffering from chronic inbreeding.

There seem to be many non-biologic, economic reasons for connection of warfare and land ownership, pointing in the same direction. First, the war brings only ruin and hardships for the majority of urban dwellers for them to start it on their own accord. On the contrary, for centuries, agrarian civilizations were attuned to co-existence with almost permanent warfare. Peasant going to war could either conquer more land or pastures in the foreign land or perish, in which case, his extended family would re-divide his plot at home. Hard-pressed burgher will likely prefer to pack and leave in search for the better. Not so a peasant, or a landlord. They can neither move their main asset, nor be separated from it, and prosper.

This argument has nothing to do with class warfare. Both roundheads and ironsides of the Civil War in England represented landowning interests with different political outlook. Great peasant rebellions in XVI century Germany and Hungary, or XVII-XVIII century Russia were led by the minor knights, or by the soldiers of fortune, hardly a serf. Chin (Qin), the first dynasty, which united China, collapsed in a series of peasant rebellions, but the victorious faction was commanded by someone Liu Bang, a minor civil bureaucrat, who then became Emperor Gaozu, founder of the Han dynasty. Certainly, class oppression stoked these rebellions, but few, if any of them had amelioration of the lot of the oppressed as an important part of their program. Dynastic troubles, foreign domination or religious impiety of the ruling classes figured much more prominently in the revolutionary rhetoric. And peasant generals frequently installed themselves in palaces of the overthrown nobility and surrounded themselves with slave servants and concubines.

Second, the accumulation of capital for the development of urbanized society almost seems to require the robbing of some agrarian order, at home or/and abroad. Britain paved the way by mass removal of tenant peasants from the estates in the late XVI-XVII centuries and later supported its own industrializing economy by exploiting of agricultural communities from North America to the British Raj. When the US achieved independence from Britain, despite inheriting boundless continent, they fought a bloody civil war and imposed reconstruction on a recalcitrant agricultural South. Yet, from 1920s to 1950s United States de-facto colonized many economies of the South and Central America in service of their own industrial development.

Not all paths from agrarian to urban society were that straightforward. Spanish Empire exploited its American dependencies, and Spaniards financed accelerated urbanization and modernization, though not in Spain, but in the Low Countries. City-states of Northern Italy, the early European leader in capital formation, were unable to subjugate or maintain significant pockets of agricultural exploitation and by the end of XVII century fell far behind their Northern cousins. In Germany, it seems that the obverse took place: predominantly agricultural, but militaristic Prussia annexed to itself urbanized and industrialized areas, first, mining towns of Silesia in mid-XVIII century, then Baden, Saar and Rheinland in the course of XIX century Wars for Unification.

Late Medieval and early Modern France was convulsing in the series of Civil Wars more or less continuously from the beginning of XV to the mid-XVII century. But given the largely urban character of later political culture in France, civil war component became subdued in all French political upheavals of XVIII-XIX centuries. Vendee was only a side show of the French Revolution. And the revolutionary age in France has ended with violent suppression of the workers’ French Commune by largely peasant soldiery of the French Army in 1871[2], after which it peacefully dispersed to barracks and farms never to return as a factor in domestic political life.

In Russia, the tsarist regime was unable to solve a development dilemma before the First World War, in part because the ruling bureaucracy was reluctant to run roughshod over agricultural interests: the landowning class still, like in contemporary Prussia and Austria, remained a backbone of the Empire’s administrative and, especially, military apparatus. Moreover, the leading landowners-bureaucrats, like Stolypin, were rather timid in their assault on traditional peasantry as well, because they perceived the peasants and their parochial outlook as the counterweight to radicalized urban working classes and intelligentsia. Only Bolsheviks with their blatant disregard for human life, established order and economic rationality, could expropriate peasantry to build their own urbanized utopia on Russian soil.

I do not suggest here, as Marxist historians in the East and West were prone to do and some revisionists still assert, that there was anything rational or even preordained in the Soviet ruination of Russian peasant society. This means, rather trivially, that the extremely violent path taken by the Russian revolution had its roots in the previous contradictions of the Empire, which entered its industrial age with more than 80% of an agricultural population. Metaphorically speaking, traditional Russian peasantry was doomed to be despoiled on the eve of 30s. However, if the Imperial military were more capable and the tsarist bureaucracy more intellectually curious, it could go down in the throes of the Depression like Steinbeck’s Okies, rather than perish in the Bolshevik terror and Stalin’s collectivization.

One must not view this rather grim outlook of the peasant societies as condescending. They were the only form possible under the economic circumstances of the times. Food, which is necessary to consume every day, had limited possibility of storage and transportation far from production areas. The only method of sustenance for civilization, i.e. a tiny elite of militarized aristocracy, with accompanying priests, scribes, artisans and merchants who were serving predominantly the ruling clique, was to resort to periodic armed confiscations in the years of scarcity. One would be hard-pressed to stop war, or require builders of the temple, or makers of the weaponry to dissolve and fend for themselves just because of draught or other inopportune circumstance. The prospects for the new technologies in agriculture were scarce. Increased productivity in the conditions of primitive storage techniques, lengthy and uncertain transportation, could only cause drastic price reductions, wiping out the economic basis of communities, which would adopt them in the years of plenty. For the peasant commonwealth to withstand systematic armed depredations of their overlords and occasional—of the nomads—it had to be organized in large family-style units with mechanisms of mutual support[3] under strong patriarchal authority. This presumed expendability of the weaker members of the community, predominantly the women.

If my reasoning is true, what this may hold for the future? First, India and China, which still have a large sector of subsistence agriculture, may be equally able to dominate our century as to collapse in bloody civil wars. Second, African continent is doomed to the continuing cycles of civil wars despite all good will and economic aid, until (1) its economies including agricultural sector will be thoroughly industrialized and (2) African cities will be transformed in the direction of the Western, business-oriented model of urbanism.

In the present state of affairs African cities are the social extensions of rustic communities. Members of the same villages and tribes populate same residential neighborhoods and maintain traditional power structures in the industrial/service setting. From the American prospective, cities of many an African nation, and the famous “Arab street”, are the federations of “urban” gangs. Like the gangs in the West, they have nothing “urban” in origin. With their emphasis of ethnic/racial origin, loyalty to a long-gone, or invented communal ideals, a hierarchy based on force and submission to a core group of aggressive armed males and collective economic and sexual exploitation of women by the members of this group, they represent a transplant of traditional agrarian order into modern industrial and postindustrial economy. [4]

Appendix A.

French banileues, which became the hotbed of Paris riots of 2005, are also quasi-village communities unlike most American suburbia. In one of the ironies, many an American suburb, which is a village in the urban planning sense, does not possess any trace of a social life of village community. Deer and raccoons may come to property in abundance, and an occasional mountain lion or a bear, and houses are all made of wood; but one’s next door neighbor may be a Chinese, another—an Israeli, third—a Korean, others—Americans from all over the continent, but one does not know anything about them. They nod politely, or ask to pet a dog; that’s it. Personal contacts are centered on professional and school networks. Common religious affiliation, which was the reason for suburban segregation in the first place, plays little or no role. The neighborhood does not define, nor does it interfere in, intimate contacts, or marriage contracts.

On the contrary, French Moslem banileue is a village, despite an artificial look of a collection of grim high rise concrete housing projects. The loyalties are ethnocentric; North Africans may mix with Turks, Bosniaks or Albanians as partners in crime and rioting, but when the contact with the “white world” around ceases, the ethnic melee immediately reforms back into ethnic crystals.

Primary groups are formed around a fundamentalist imam as an extension of a village elder. Sister of a member who goes outside of the network for dating is defamed and severely punished. Former members of the community, who prospered socially and financially, are long gone and remember their former origins with a shudder, not too dissimilar to the residents of immigrant ghettoes of XX century America. Remaining are unemployed, semi-employed or work in a local economy; their professional position is neither a sort of identification, nor of a particular pride. Traditional villages probably had some internal hierarchy based on relative level of prosperity and/or strict or lax adherence to the morality norms[5] of the collective, but the nature of agricultural labor was common for them all and imposed an artificial uniformity on their already drab existence.

Appendix B

If the above reasoning is true, civil wars in Africa and in the Middle East cannot be reduced with economic aid. In fact, most disastrous civil wars happened in countries such as England (War of the Roses and Cromwell Revolution), United States (1861-1865), Argentina (large part of XIX century) and Russia (1918-1920), which were at the time major food producers and exporters and did not suffer from agricultural shortages per se. In some of the above cases abundance could have actually increased because of the reduced possibility to export surpluses.